I wanted to re-read The Great Gatsby. Like you, probably, I had read the book in high school and not since. And, perhaps like you, I had a decent recall of the story but a fuzzy memory beyond that. There were the giant symbolic spectacles on the billboard; the shadowy character of Wolfsheim; the important critical notion of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “unreliable narrator” who tells the novel; and the mystery, revealed quite late, of Gatsby’s true identity. I wanted to refresh myself, and a good thing, too, as it turns out a number of these residual impressions had been wrong. More on that soon.

The Great Gatsby is rather short, as you know, and I went on to read, I’d estimate, half of Fitzgerald’s published works. He was extremely prolific during his brief lifetime – he died at 44, the age I am now – and I wanted to burrow around, especially among his short stories and essays, for which he was amply famous while he was alive and which, if I am keeping score, I had previously encountered probably only through a handful of titles, some of which will doubtless ring bells for you, as well – how about The Diamond as Big as the Ritz, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” and maybe even “Winter Dreams,” a story about a young man courting a wealthy girl, which is the plot of approximately 40% of what Fitzgerald published. “Winter Dreams” is of special interest because it was inspired by Ginevra King, a Chicago debutante socialite with whom Fitzgerald had an essential affair at a young age and who sent him a story about a rich woman trapped in a loveless marriage who was finally free to live with her true love after he gained enough wealth to secure her life. Yes, I can see your head nodding, that does sound familiar: Ginevra King also inspired Gatsby’s Daisy Buchanan, and it is has long been well established that his novel paralleled his ex-girlfriend’s story.

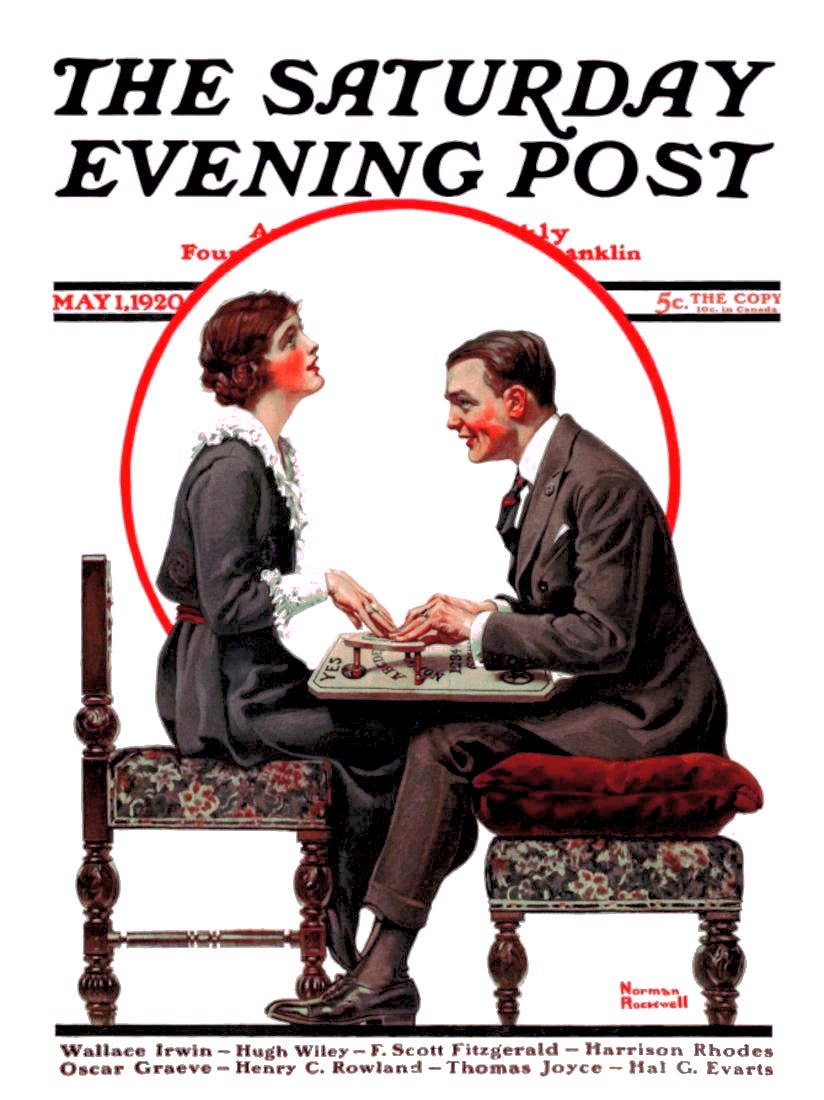

Fitzgerald’s short works are nowadays deprecated – no, that’s not right, they have always been deprecated and continue to be deprecated – as compared to his novels. During his lifetime, This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and the Damned made him famous among the public and the critics alike. This Side of Paradise, published in 1920 and the first of his four full-length books, flew off the shelves. H.L. Mencken, the dean of American letters, lavished praise. Fitzgerald was instantly famous. His previously rejected short stories were now accepted, at lucrative pay scales, by the big magazines. The Saturday Evening Post published “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” with an accompanying cover illustration by Norman Rockwell. Two years later, The Beautiful and the Damned, his second novel, gave him another smash hit. Both featured Ivy League graduates flapping around in flapper New York. (There must be some kind of prize or penalty for this kind of reductivism, but to hell with it, I’m making moves.)

It is regrettable, but it is regrettably true, that all of this should prove to be preamble, in the considered eyes of the last eighty years, to Gatsby. Gatsby is Fitzgerald’s all-time legacy, his most accomplished accomplishment. This is what we have learned. But at the time, it wasn’t nearly so successful. Published in 1925, The Great Gatsby was actually a commercial and critical disappointment, selling far fewer copies than its predecessors and receiving mixed reviews. For the most part, the commentating class, while admitting to being impressed with the evolution of Fitzgerald’s style, were non-plussed by the result. In fact, the throughline from the smart money was that Fitzgerald’s already-evident decline in the Beautiful and the Damned was now further in evidence. They did not like the plot. They did not believe the characters. They did not find the novel credible. And though a bunch praised the prose, they found the book inconsequential. Fitzgerald was angry and resentful. He felt misunderstood. Adding to the injury, Gatsby generated precious little income for him. For the perennially teetering and broke Fitzgerald, this was perhaps the worst part.

His final novel, Tender is the Night, was the coffin nail. Like Gatsby, Tender is the Night has grown in stature over the years, but it received a tepid response when it appeared. Fitzgerald had worked on it for almost a decade, starting right around the time Gatsby was released in 1925, and by the time Tender was published in 1934, after the Great Depression had already been ravaging the United States for five grueling years, the reading public had lost its taste for yet another story about rich people living execrable lives in glamorous places. The Jazz Age was well and truly dead, yet Fitzgerald was apparently still steeping himself in it like a Gibson onion in a bathtub gin martini. Doubtless this alienated many. We will not treat of Tender in this essay, but it is probably helpful to note that this novel was a book-end to Fitzgerald’s decline; that it was considered a failure by most of his contemporaries; that it is, together with The Beautiful and the Damned but by far more so, the source of much understanding and speculation about his wife Zelda and about his relationship with her; and that it was bucketed with Gatsby both at the time as a misfire and, later, as one of his two greatest triumphs. After Tender is the Night appeared, Fitzgerald’s alcoholism, already in full flower, overran his life, and he was given little attention for his final half dozen years. In the decades since his death, his friends like Hemingway (you can read my analysis of Hemingway here or listen to it here) whom Zelda seems to have blamed for turning F. Scott into an alcoholic and thereby sapping his energy and productivity, and his critical champions like Mencken, resuscitated his reputation and moved Gatsby and Tender from the bottom of his headstone to its top. This has happened countless times in literary history, and I am sure you can name many. My favorite example is Herman Melville. Typee, Omoo, and Mardi, his first books, blew the doors off when they were published. They enjoyed record-breaking sales and were hailed as proof of the arrival of an American literary legend. These books are, finally, unreadable. By comparison, Moby-Dick, our country’s most important romance ever, barely sold at all when it was published a few years later. It was panned. Baruch HaShem, we fixed all that good. But if it could happen to Herman, it could happen to anyone. And so it happened to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

And this is why we think of Fitzgerald the way we do. Our entire received opinion and consciousness of Fitzgerald are the products of this moment of rescue, now about sixty plus years old. Everything has followed from it.

Let us consider: what do we think when we think of F. Scott Fitzgerald? The first thing is Gatsby, of course, and something to the effect that he was the Jazz Age bard, and then maybe that he wrote Tender is the Night. Quickly we recall two biographical facts: he was a terrible alcoholic, and his wife was insane. You might have your own list, but I’d bet a pitcher of ice-cold Tom Collins it’s pretty similar. Probably even the flapper era short works that we read in school don’t appear to the mind’s eye without prompting. And almost certainly, his massive body of work as a magazine writer does not figure into our conception. This, finally, is a miss.

Time and time again, and in no case more so than in Fitzgerald’s, we have been let down by our critical class. F. Scott Fitzgerald is so much bigger than they, in rescuing him, made him out to be. He is so much better than The Great Gatsby. His greatness can be measured in spite of The Great Gatsby.

Reading widely in Fitzgerald leads to the obvious conclusion that he was one of the very greatest writers America has ever boasted. The non-obvious conclusion is that he was so exceptional not just because of a particular masterwork, which does not do him justice, but because of his vast breadth. In particular, more than any other American writer of at least his era, he possessed a devoted interest in and a stunning capacity for understanding, grappling with, and mastering element after element of literary excellence. He studied writing and committed to the project of versatility in its art. I cannot think of an author with greater command of so great a range. Can you? A handful of critics of his own time made similar sounds in respect of his novels. But his short stories – which I have become convinced are essential to any coherent picture of Fitzgerald’s writing career or indeed of his own self-conception as a writer – have been omitted from the frame, and his enormous breadth remains the unappreciated marvel of his exceptionalism. The professional literary critical undertaking of the latter 20th century fails cases like his, as it seeks to isolate and elevate digits and limbs in place of and over the body. They want us to know him as X or Y but not as A to Z. I guess this kind of atomization gets some people tenure.

Let us be more specific.

Through the years, Fitzgerald has been examined through a variety of critical lenses that more or less cohere in the following handful:

Fitzgerald has been viewed through the psychological lens, which usually looks something like this: he was a tortured self-conscious parvenu scrambling for East Coast acceptance, struggling with midwestern Catholicism, fitfully regretting a marriage to a bipolar wife (she was then viewed as a schizophrenic), flailing about with socialites, declining in his acute alcoholism.

He has been deemed a commercial compromiser: writing sellable stories instead of high art in order to fund an expensive lifestyle. This is one of the chief reasons his stories are often dismissed. You’d think it would be the opposite: if most of the stories were poor, they could be shrugged off. Then the conclusion would emerge that he compromised there to fund his art and life here. But I think it’s the other way around: we ignore his stories because they were commercially so useful to him. The critical class long ago decided that his stories made him too well-paid, too famous. Therefore they must have been bad.

Fitzgerald through a political-social-scientist lens. One of the most important charges that the cognoscenti have brought against him since his own time was that he “had no intellectual ideas.” He was not interested in political activism or in the major matters of the day. He did not pull an Émile Zola. He ignored the headlines. He wrote about rich people during the most devastating economic decade in memory. He did not champion the underdog. It is a largely accurate accusation, and it was enough for his contemporaries to develop contempt. This contempt produced an inaccurate corollary or, better, an inept broadening of the indictment: that Fitzgerald had no ideas. He did. Big time. He had ideas about writing. He had ideas about being American. He had ideas about virtue. But, again, once you see him through this well-characterized lens, you don’t need to bother with the great bulk of his work, as it appears to be mostly Douglas Fairbanks saber flourish and Boston Pops chestnuts for the popular rags.

Fitzgerald as not-Hemingway. F. Scott was the other one, the other incandescent star of the 1920s. This take has a few forms, which highlight some combination of Easier Sentences, More Naturalistic Language, Less Overt Ambition, Better Actual Writing, and Less Showy Manful Trout-Fishing Extravagance. You get it.

Then there is Fitzgerald the author of The Great Gatsby, America’s perfect novel, the one you read in high school and in which you discovered symbolism (remember the giant spectacles on the billboard and the cascading colorful shirts in his closet?) and the unreliable narrator. This one deserves more attention. It is – whether standing by itself or as a component – at the core of everything we know and think about Fitzgerald.

So much of what I thought I had recalled and appreciated about Gatsby turns out to have been misremembered and misplaced. As I mentioned, I started out on this Fitzgerald journey because I wanted to re-read this particular novel. I had felt a longtime affinity with it, not just as a reader but personally, from various episodes in my life that started with the first encounter in high school. I lived for an important, formative time in my life in Louisville, Kentucky, where critical flashback scenes unfold as Jay Gatsby meets Daisy Buchanan, and where Fitzgerald slept and wrote — in a building about three yards from where I came to live ninety years later. I remember walking along Cherokee Parkway some nights in May, thinking about those scenes from the book, smelling the sweet scents of warm evening weather peonies and freshly landed love. Very recently, I stayed in Deauville, France, where Tom and Daisy Buchanan passed part of their honeymoon and which, just as much as East Egg, is a metonym for their life. The trip to that historic town was, in fact, the reminder that prompted me to pick up this book once more. I am very glad I did, because it led to so much. However, in my view, Gatbsy itself does not, finally, hold up to re-reading and reconsideration.

A first observation, just a simple observation that may be obvious to you, if your memory of the novel is better than mine was, is that the book is really the story of Daisy and Tom. It’s not about Gatbsy. In fact, Gatsby barely figures in it. The same goes for the narrator Nick Carraway. It is not his story, and it is only very barely his story to tell. The book is about the husband and wife.

Second, it is time to set aside the myth that Nick is something magical and important called an “unreliable narrator.” He is certainly not fully drawn. I think this is often viewed as evidence of his being unreliable. We are supposed to discover in Gatsby, as teenage American readers, the concept of an “unreliable narrator” and to locate the intellectual origin of that literary device – in our education, if not in literature – in this book. This holds no water. It is more accurate to conclude that Nick’s portrayal was just inconsistent, which is to say that he was inconsistently written by Fitzgerald. We see it even in his internal dialogue. Sometimes Nick cares about this or that value system. Sometimes he does not. Sometimes he stands up for himself, and sometimes he does not. We can find, at most, weak explanations in the particular circumstances the plot moments might afford us. Nick’s perspective on himself, on others, and even the lenses through which he views both, shift and disappear and reappear in short order, in short time, and in quick sequence, and without explanation or background justification. You’d need to stand on your head on a flying trapeze somewhere on the dark side of the moon to perceive this as Fitzgerald’s intelligent design. With a modicum of emotional distance and with a fresh pair of eyes over which are wrapped a pair of overtly symbolic spectacles, you can see it for what it was, as a set of errors, especially since other, similar gaps appear in the book. Take, for example, the fascinating, promising character of Jordan Baker, the “incurably dishonest” sportswoman and Nick’s romantic interest. About two-thirds through the novel, Fitzgerald just drops her from the scene. She was integral to the story, perhaps the best drawn character in the book; the most exquisite exemplar of the underbelly of the milieu into which Gatsby sought to ingratiate himself; a mirror unto both Daisy and Nick; a plot-level useful purveyor of critical information; and the most interesting thing about Nick himself. Then, all at once, she just ups and disappears from the pages, without explanation. I have not yet been able to cook up, and I have not yet encountered, any useful or satisfactory reason for this sudden dropping of a ball that would make sense either for Fitzgerald or for Carraway. I think we should see it for what it is: just a plain old mistake.

Similarly, the book is stylistically rather diverse throughout. This is true of Fitzgerald‘s work as a whole, and his extraordinary breadth is one of his signal achievements. But, within the four corners of Gatsby, this diversity of style does not appear to serve any particular purpose. I was first struck by the appearance of a handful of difficult short passages at the very beginning, which then give way to remarkably easy reading. As the book goes on, the style varies from casual and breezy to stilted and formal without connection to the context or the moment of the narrative. Why would Fitzgerald – set aside his creation, Nick – have made it so?

The gray zone between the Long Island Eggs and New York, the Valley of Ashes, where live Tom’s mistress Myrtle Wilson and her husband, is a kind of comic book hell, too convenient and implausible. I understand this enormous refuse dump was based on the Flushing Meadows landfill, which was apparently pretty horrible, so I think my impression of its implausibility might be provably wrong. Fitzgerald may have been inspired by the real deal. But the depiction of the dump, its size, its odor and odiousness, is certainly heavy-handed and, finally, obvious. The lifestyles that one finds in the Long Island Eggs and in Ritzy New York City are made possible by the seedy, smelly supply of sex and labor that the rich can steal from the squalid No Man’s Land in between. Get it? Woah . . . . Symbolismmmmm . . . . You would be forgiven for imagining the scenes taking place in the Valley of Ashes as accompanied by a vaudeville stage, on which the curtain rises to reveal a strongman holding above his head a half-ton barbel. A sign comes down from the ceiling: “HEAVY!” Don’t you see? Do you not see? It is heavy! Symbolism!

Indeed, I was struck by how obvious Gatsby repeatedly was. I think the symbolism that I recall thinking that was there when we read it in high school or whenever was really not. The shirts being thrown in the closet maybe like tears or insubstantial wealth baubles were not moving nor arresting nor interesting. The symbolism of the glasses on the T. J. Eckleburg billboard was not in fact at all implied or hidden but instead overtly expressed by Fitzgerald as a metaphor for the eyes of G-d. Gatsby himself, the character whose history is the catalyst for the story and whose life has been spent hiding his past, was far less of a mystery then I remember his being. His identity is effectively entirely revealed about halfway through the book. I suppose this is all a great fit for American high school readers. It is not overly nuanced, one can say. For teenagers developing their critical eye and vocabulary, the degree of difficulty seems sensible. Faint praise, indeed.

So much for The Great Gatsby lens through which to view Fitzgerald. It is not and has never been his singularly best or most important work. The success of the Academy in rescuing and elevating Gatsby has been too complete, and it does and should betray our confidence. We have to slough it off, alongside the other lenses they have given us to appreciate Fitzgerald.

It is instinctual to read the other fellow’s remarks through the frames of whatever billboard spectacles are at hand. Pick your prescription: American exceptionalism, Diversity & Inclusion, The Decline of Western Civilization, White Supremacy, Futurism, Marxism, Scientism, Atheism, Rationalism, Capitalism and Its Discontents, Socialism and its Make-Beliefs, Gender, Climate, the Gig Economy, the Maker Economy, and that most singular and influential organizing principle of all, Femto-Management.

What if we took a more phenomenological approach: what is the thing sitting there on the desk, the item actually waiting to be read?

We immediately notice Fitzgerald’s versatility. He could write funny, morose, silly, dark, exciting, calming, drily wry, fiercely cutting, drama, comedy. He could hide or parade his coruscating social criticism, but it was usually there. He could write a happy ending or a gloomy one or none at all. He could write about rich people, or rich adjacent, or about the poor and middle classes. And he did all of it well. Over and over, he delivered.

Fitzgerald is conventionally known as a glum observer bumping along in a melancholy marriage with a mentally ill wife, and this received perspective informs the typical imagination of his novelist’s voice as a distant, detached eye, regarding the action only half-willingly and in caliginous crepuscule. (There’s at least one five-dollar word there, and I hope you enjoy looking it up as much as I did.) But it is time to discard this perspective of Fitzgerald forever. Whenever he wanted, he could be hilariously funny. “Myra Meets His Family,” a short story published in 1920, begins like this:

Probably every boy who has attended an Eastern college in the last ten years has met Myra half a dozen times, for the Myras live on the Eastern colleges, as kittens live on warm milk. When Myra is young, seventeen or so, they call her a “wonderful kid”; in her prime — say, at nineteen — she is tendered the subtle compliment of being referred to by her name alone; and after that she is a “prom trotter” or “the famous coast-to-coast Myra.”

That same year, shortly after the publication of This Side of Paradise, he wrote “An Interview with F. Scott Fitzgerald.” The conceit is that he, F. Scott Fitzgerald, hunts down F. Scott Fitzgerald at his hotel to land an interview about his writing and ambitions. Here are the opening lines:

With the distinct intention of taking Mr. Fitzgerald by surprise I ascended to the twenty-first floor of the Biltmore and knocked in the best waiter-manner at the door. On entering my first impression was one of confusion — a sort of rummage sale confusion. A young man was standing in the center of the room turning an absent glance first at one side of the room and then at the other.

“I'm looking for my hat,” he said dazedly, “How do you do. Come on in and sit down on the bed.”

The interview reveals the able hamming of a breakout star and the self-deprecation of a young man unsure that he’ll ever pull off whatever it is he wants to pull off. It also contains some of the most candid admissions of his hopes for a writing career, to which I’ll return shortly. Fitzgerald intended this interview as a publicity lark for This Side is Paradise. Scribner’s didn’t end up using it, and it languished – in its original pencil-on-paper written form – in the Scribner marketing department desk drawer for forty years until it was rediscovered and published in The Saturday Review, which was a kind of essential periodical for educated Americans for four or five decades until it died, like a clutch of its ilk, in the television era.

“The Dance” was a tongue-in-cheek murder mystery, set in the South. It reminded me of Peter Taylor or Eudora Welty or Elizabeth Spencer (you can find my piece about this essential Southern writer here), but it could also have been an episode of Columbo or Murder She Wrote. Fitzgerald could likewise do bathos, which isn’t itself a tenor necessarily worth praising, I think, but which is yet a kind of breadth. “The Smilers” is a good example. Fitzgerald wrote this rather didactic, moralizing story, about people who may or may not fake-smile their way through difficult days, right around the time This Side of Paradise was accepted by Scribner for publication. He submitted the story to Scribner’s Magazine shortly after, and it was rejected, which has got to be almost perfectly incredible. Less successful was “The Adjuster,” about a high-flying sort of woman whose husband and son fall sick and who is taught to grow up to handle adult responsibilities by a mysterious figure known as, you guessed it, the Adjuster. It’s a good idea and a sympathetic story of transformation, but later readers will have had the benefit of Bernard Malamud, who did this particular trick far better than Fitzgerald. I wondered if Malamud had been inspired by “The Adjuster” for his 1958 story “The Magic Barrel,” in which the crypto-angel character Pinye Salzman, the shadkhan, plays a similar role.

Fitzgerald published a fair few of what you might call Happy Ending stories like “The Popular Girl,” who, it turns out, is loved by the boy of her dreams even if her father’s death has left her in unexpected tough financial straits; “The Adolescent Marriage,” in which a young couple frustrated with each other are saved from their would-be divorce by a wise old architect; and “Not in the Guidebook,” about two star-crossed lovers who are, finally, reunited after a terrible and predatory wartime identity theft is uncovered and rectified. Among these Happy Ending stories, there is found a considerable number of the “I am secretly richer and kinder than I previously let on” variety. Think Charles Dickens. Of course, more than that, there is a long history of this literary genre of what used to be called, in the old days, Comedy. But I wonder why Fitzgerald did it so often. The fact defies obvious casual explanation. For example, he did not start publishing these during the Great Depression, when some nice uplift would have likely made readers’ days a little brighter, but instead almost as soon as he started writing professionally, as early as his twenties, about a decade before the Depression started. The frequency of this type of plot – well, of this type of ending, with a healthy variation of lead-ins to its sorbet sweet flavor of cheerful endpoint – made me wonder if it was a genre that was especially popular at the time or whether Fitzgerald himself helped make it so and whether the feel-good story was kind of one of his brands while he was in his ascendancy. I don’t know the answer to this question. In any case, you can see the Serious People dismissing this part of his corpus as mere Hallmarkism. It isn’t. I don’t countenance the instinct to deprecate an upbeat ending – any more than anyone can possibly understand why the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences doesn’t seem to find comedy, comedians, or even joy worthy of Oscars. In fact, some of Fitzgerald’s most precious characters, devices, and moments can be found in such stories. But over the years, they got a bum rap.

If we were pressed to explain why they got a bum rap, and if we were not allowed to cast all the blame on snootery, we might point to the apparent repetitiveness of some of Fitzgerald’s most famous themes. If you were to dip into his short stories at random, you would be forgiven for getting the impression he wrote the same story over and over again. Glasses tinkle. Harvard, Yale, or Princeton graduates circulate. Protagonist joins city clubs. Hangs around the Ritz. Drinks a lot. Sells bonds. Bops around in cars. Takes apartments or hotel rooms on high floors or calls on ladies on other high floors. Finds himself under pressure. Wife finds her courage. Man misses what he wanted most. Everyone just barely holding back the dyke of debt and ruin and expenses and divorce. Searches for finer feelings. Chickens come home to roost. Fin.

The fact is, he did write a lot of stories in this basic outline. He often featured a fast motorcar, a handful of evening clubs, a fancy college, and either the Ritz or the Plaza. This glamorous collage was clearly useful to him, both to entice and to turn off the reader. I don’t know why so many characters visited the Ritz and Plaza in particular. I have spent a modest amount of time researching this subject, and I still don’t think I have a compelling answer. Perhaps one of the cultural historians among you will be able to fill in the details. The high line is probably simple: both the Ritz and Plaza were glittering and prestigious at the time of Fitzgerald’s writing, and, of course, grand hotels were hubs of swank social life. I did learn that they were both also at least kind of artifacts of the moment. The Ritz opened in 1911, a couple of years before Fitzgerald went to Princeton. It must have been quite the thing, and he must have torn it up there rather often. Likewise for the Plaza, which was completely rebuilt in 1907 into the iconic structure we know today and then expanded smack dab during Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise heyday years by the same architectural team that had designed Grand Central Terminal a decade earlier. The Plaza’s reopening must have been the full business at the time, generating as much press as any other going-on of the Who Did What When With How Much variety. Not only was it glamorous and semi-realistic to waltz his characters through these rooms, but it might have done for his works what filming at the Burj Khalifa did for Mission Impossible 4. In Fitzgerald’s hands, these settings, though repetitive, rarely sound a false note. The characters nearly always belong there, either through desert or ambition. An exception, in my view, is not found in a short story but in the famous scene from The Great Gatsby, in which the principal cast trundle into New York City, take a suite at the Plaza, and do battle. The entire episode is implausible. They visit the Plaza for just the blink of an eye, and there is no plot-borne reason for them to be there. Had Fitzgerald had some kind of rule that every single story must mention the Plaza or Ritz, one could be satisfied. But he didn’t. Most of his works had nothing to do with such places. In Gatsby, it just seems the Plaza was a concocted and convenient destination that required everyone to get into a car and cross the Valley of Ashes.

These New York City institutions make far less gratuitous appearances in Fitzgerald’s other writing. And it is clear that, for quite a long time, there was a nexus between the Ivy League super-monde and New York hotels that would be difficult to imagine – or even to believe – today. Bertie Goelet, a giant in real estate, from a family so wealthy and influential that he was a household name – think Bloomberg or Trump – and whose name seems to have disappeared entirely from public life since, but anyway a billionaire at the time, with vast holdings in the United States and Europe, personally owned the Ritz-Carlton Hotel at the time of his death in 1941. In his will, he left it to Harvard, his alma mater. Think about that. The man bequeathed the Ritz Hotel to his old university. Could you imagine that happening now? Could we imagine Mark Cuban bequeathing the Dallas Mavericks to Indiana University? Or Mike Bloomberg donating the building where his eponymous company works to Johns Hopkins? No, I can’t imagine that, either. No one can. But, in Fitzgerald’s time, there really were eddying circuits of revolving doors among prep schools, Ivy League fraternities, law firms, banks, city clubs, and glowing venues of gentle mixed-gender recreation. This Side of Paradise indeed.

It may surprise you to learn that most of Fitzgerald’s short works were set outside of this closed loop. A striking example is “The Pusher-in-the-Face,” which very much takes place in the streets of New York. It is a story of pluck and brio and the little guy. It wouldn’t necessarily play well today, but it was very popular at the time, with many republications in various collections. The opening finds the protagonist in custody awaiting his hearing for a minor assault. He defends himself to the presiding magistrate by explaining that he did, indeed, push a lady in the face, but only after such an exceptional campaign of aggravation on her part that the shove could only be deemed justified. The judge agrees! Our shy, mousy hero, vindicated and released, feels emboldened enough to become a temporary streetwise vigilante, redressing slights and insults and even police wrongdoing. During the half dozen years after its first publication, “The Pusher-in-the-Face” was released several times, including in an illustrated version, and then made into a movie in 1929, a short, starring a cast that was rather famous then but no longer, including Reginald Owen, an actor whom you might recall as the Admiral Boom from the original Mary Poppins starring Julie Andrews – you remember, the old Navy man who commands that a cannon be fired from his rooftop ship deck every evening at 6 pm.

Another important example of a story that takes place far from East Coast glamour is “Absolution.” Rudolph Miller, an eleven-year-old, is growing up in a punishingly strict Catholic household. His father almost gladly beats him for any transgression of religious obligation. He has an active escapist fantasy life, imagining that he is Blatchford Sarnemington, a young man of “suave nobility” who “lived in great sweeping triumphs.” Miller is seeking to make an informal confession, in the private office of Father Schwartz, who is sitting behind his “walnut desk . . . pretend[ing] to be very busy.” The precipitating event of this short story is that the boy told his father he had sipped water on the morning before a recent communion, which, in the eucharistic discipline, obviates the holy sacrament. Not only this, but he has lied at a prior confession. Miller, finding himself in spiritual crisis under the terrible weight of these secrets, comes clean to the priest. Until this point, Fitzgerald’s story is quite perfect. He recreates and captures the distress of a young boy under unspeakable pressure. The prose is sincere and spare. The characterization is so pitch perfect that you can’t help but believe Fitzgerald knew this boy very well. At the end, though, the story falters. When Miller blurts out his confession, the priest inexplicably collapses, and the story abruptly ends. Fitzgerald did this from time to time, I think: he neither provided an explanation for the action (here, the sudden collapse of the priest) nor provided enough contours for the reader to fill one in usefully nor offered enough even tectonic-plate-level notions for the reader to claim an intelligent right to imagine one. This is, for him, a rare characteristic literary pitfall, I think. It’s almost as if Fitzgerald got bored with the material and didn’t want to finish it, and he knew he could get away with half-assed nonsense because some educated idiot or another with a cigarette twixt her fingers in a first floor Brooklyn apartment would gleefully insist that this obvious mistake was “genius.” To make matters worse, “Absolution” ends with an unhelpful change in idiom, switching from clear narrative toward something like a dream sequence.

Nevertheless, this story is utterly important. Not only because it is an excellent example of Fitzgerald’s many pieces in which not a diamond nor a Ritz is ever in sight, but because of what “Absolution” was originally supposed to be. You might have guessed it already. Let’s review the key facts. A young Catholic boy fantasizes about escaping his reality by becoming a dashing WASPy adventurer. Doesn’t that sound familiar? Yes, you are right! Fitzgerald intended “Absolution” to be the prologue to The Great Gatsby. He excluded it from the novel for reasons that are, I think, mostly lost to time, though he offered some explanations over the years that are not quite satisfactory. He said once that he wanted to preserve the mystery of the Gatsby character. That would make more sense if the book preserved the enigma till the end, as it did in my memory, rather than till some time in the early middle, when it is explained. He remarked on another occasion that the putative prologue did not fit with the “neatness of the plan” for the novel. By itself, that doesn’t say much. But I think I can propose an explanation, and I think it points to something essential about this writer that has not, I believe, been observed till now.

I believe Fitzgerald observed the unities. He was a classical writer who regularly subjected himself to the constraints of the three unities of Aristotle. Bear with me. I believe I have come to understand a quality of his writing that allows us to comprehend and appreciate him more deeply. Let me make the case.

First, let’s refresh on these three unities, often known as the classical unities or the Aristotelian unities. They were rules for the coherence, beauty, and importance of a play, which really meant a tragedy. The Unities were:

1. Unity of Action: the story should have one major event or plot throughline.

2. Unity of Time: the action should unfold over one day, or 24 hours.

3. Unity of Place: the action should take place in one location.

The Unities are typically attributed to Aristotle because he describes them in his Poetics and Rhetoric, but they don’t really belong to him, not as they have come down to us. The Unities as we have them were more or less conjured or codified by a sixteenth century Venetian named Gian Giorgio Trissino, an oddball kind of ultraconservative political and literary figure who, while aggressively humorless in his extreme and adamantine critical taste and while both ardent and feckless in his religio-political allegiances was either surprisingly likable up close or feared in the way that some thinking people are able to disguise as respect, because no matter whom he betrayed – he betrayed popes and kings and their acolytes up and down the ranks, on the regular – he never quite fell out of favor with his rulers. Trissino put forward the Unities as a recovery of Aristotle’s critical comprehension and instruction. His proposal to adopt these Unities was culturally successful. What followed was a desiccation of Italian theater. The Trissino school wrote boring, moralizing, declamatory plays, including when Trissino himself was the author. Theater was suddenly unfun. Nonetheless, academies of late-Renaissance-early-Reformation Europe were quite taken with the purported recovery of Aristotle’s precepts, and the adoption by playwrights of the Unities’ formalisms became de rigueur. After a while, they grew quite tyrannical, crystallizing as the chief yardstick by which creativity and skill were judged. It was a serious time. The unforgiving strictures of the Unities mostly ruined theater for about a hundred years, probably until Pierre Corneille rescued it with Le Cid in 1637, which in large part because of its violation of the Unity of Place and its stretching of the Unity of Time and perhaps even the Unity of Action, along with its rejection of the tragedy-comedy binary and at least one character’s jarring ethical choices, scandalized and then revolutionized the entire thinking life of France. The just-formed, brand-spanking-new Academie Francaise, established and administered directly by Cardinal Richelieu himself, made a symposium on the exact subject of Corneille’s new play. The very public debate featured broadsides by the Academie’s most eminent figures and France’s other celebrated dramatists, as well as equally vocal defenses by Pierre Corneille himself. Though the Academie Francaise acknowledged the strengths of Le Cid, its ultimate judgment was one of deprecation for moral, stylistic, and formalistic reasons. Nevertheless, the water was over the dyke, and Corneille had smashed the strictest tyranny of Trissino’s Unities forever, such that later playwrights, including his countrymen Molière and Racine, could choose to adhere to, ignore, or play with them, as might most fit their ambition. It was probably this loosening of the most severe interpretations of the Unities that not only saved them but gave them the greater measure of force, for suddenly they were like manners, which mean a great deal when observed and even more when the knowledgeably observant choose, finally, to lay them aside. Over the centuries between Molière and now, the Unities have continued to lend power to authors who observe them. This is true both because any well articulated structure and suite of artistic rules gives more life to its practitioners (see here and here and here, for example, for the rules from a rather contemporary art form, the noir novel), whether or not the audience is strictly aware of those rules, and because the most ambitious writers of every generation for four hundred years have wanted to test their mettle against the worthies of the past. It is nevertheless true and clear that, over time, fewer writers have shown overt and particular interest in the three Unities of Aristotle.

I make the case that Fitzgerald was one of them. I make the case that Fitzgerald understood that he was at his best when operating within codes, and in fact that he knew he was excellent enough to thrive when signing up for boundaries. In the same way that favorite poets would exhibit their prowess and wild diversity within the tight confines of an ode or elegy or sonnet, in the same way that dramatists would flourish their freedom and dexterity by agreeing to the precepts of Aristotle, he, too, could and would prove how extraordinary a writer he was by brandishing his versatility in spite of similar constraints.

This is easiest to perceive in his short stories, which confine themselves to single actions, often places, and almost always very short periods of time, usually measured in hours or days or sometimes weeks. Objectors might point out that short stories are usually like this, given the limitations of the form, though they’d be making the case for as much as the case against. Ample evidence is found in Fitzgerald’s novels, too. The Great Gatsby takes place mostly in a concise period of time, mostly in something like Greater New York (admittedly not a drawing room, but hardly a prance about the continent), and there really is only one action.

I believe it is for this reason that Fitzgerald omitted from Gatsby the prologue that was eventually recast as the short story “Absolution.” The “neatness of the plan” that he did not wish to disturb was the bundle of temporal and thematic unities that was so tightly wound in his novel. Fitzgerald’s storytelling is notable for its classical immediacy. The action is right now, right in front of you. Even the past is unfolding in the right now. Throughout his corpus, he sometimes has an allusion to a post-script or pre-script or an incident that took place before, but it is almost always about as long as a paragraph. The past is immensely important, but the action today is where we focus our eyes. His books are not what you would call sprawling. Many writers of his period – and before and since – staged their stories over years or decades. This is, on balance, rather unusual to find in Fitzgerald, and certainly there is no epic, cascading ambition of narrative, no interconnected or parallel parties, no warring tribes, no grand reverbs over the centuries or generations. He can see his way clear to a boat and a transatlantic war, but even then the action is small and personal, not imposing or sweeping, and it mostly exists to impact what happens later, in the now-time.

Objectors will point to flashbacks. Fitzgerald does use flashbacks liberally, including, as it happens, in the short story “Absolution.” But they are nearly always remarkably brief, sometimes preciously so. Nonetheless, the purists of the Academie Francaise variety will point out that flashbacks violate the Unity of Time. I think I don’t have to answer them. Pierre Corneille did that already almost 390 years ago.

Fitzgerald did his best driving inside a set of rather stiff running boards of Aristotle’s or Trissino’s devising and of his own peculiar manufacture. Time and again, he visited with motorcars and Ivy League ties and strong cocktails imbibed by bond men inside the self-same unity of city clubs and Ritz-Plaza hotels. Even more frequently, he led his characters through tight stories on short time fuses. And, with even more frequency still, he reminded his readers of good old-fashioned American bourgeois values, like honesty and hard work. I love his playful contempt, in a short story called “The Sensible Thing,” uttered in the mind of the narrator with a stone cold straight face but gushing with irony from Fitzgerald-on-high, for the sacred belief, among the character’s aspirational social class, that “success is a matter of atmosphere.” Fitzgerald’s works also, from time to time, brimmed with his happy and enthusiastic patriotism. Perhaps my favorite example is his comment on the opening setting of one of his stories, an eastbound cruise liner: “Hope is a usual cargo between Naples and Ellis Island, but on ships bound east for Cherbourg it is noticeably rare.” In a letter to his daughter written some time toward the very end of his life (the letter reveals that it was penned when she was about to start the college semester, and he died when she was nineteen years old), Fitzgerald wrote about a sometime ambition to have been a musical theater composer like Cole Porter. After making some noises about the possibility, he concludes that this route had really been impossible for him, because he had been “too much a moralist at heart, and really want to preach at people in some acceptable form, rather than to entertain them.”

Fitzgerald’s versatility blossomed in these well characterized, hemmed conditions. He wrote broadly across subject matter but even more broadly across styles and techniques. This was deliberate. In fact, it was a chief and defining objective of his writing life.

In the “Interview with F. Scott Fitzgerald” that he wrote in the wake of This Side of Paradise, he put versatility front and center in his life’s writing mission. The journalist Fitzgerald quoted the subject Fitzgerald thus:

I want to be able to do anything with words: handle slashing, flaming descriptions like Wells, and use the paradox with the clarity of Samuel Butler, the breadth of Bernard Shaw and the wit of Oscar Wilde. I want to do the wide sultry heavens of Conrad, the rolled-gold sundowns and crazy-quilt skies of Hichens and Kipling as well as the pastel dawns and twilights of Chesterton. All that is by way of example. As a matter of fact I am a professed literary thief, hot after the best methods of every writer in my generation.

This interest remained essential for Fitzgerald for the rest of productive writing life. You can see it in his private correspondence, in which he celebrates various authors while evincing clear understanding, as many excellent writers do in private correspondence or essay, of such and such an author’s particular strengths or otherwise. In a letter to his daughter written in the very twilight of his life, he offers a muscular rip through a handful of authors, precipitated by an ongoing reading of Tom Wolfe’s new book. Here, of course, he means Thomas Wolfe, not Tom Wolfe of Bonfire of the Vanities. Based on the timing and content, I think he means Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again, which was published in 1940. That means this letter, which has come down to us undated, would have been written in the final months of his life:

I started Tom Wolfe’s book on your recommendation. It seems better than Time and the River. He has a fine inclusive mind, can write like a streak, has a great deal of emotion, though a lot of it is maudlin and inaccurate but his awful secret transpires at every crevice—he did not have anything particular to say! The stuff about the GREAT VITAL HEART OF AMERICA is just simply corny.

He recapitulates beautifully a great deal of what Walt Whitman said and Dostoevsky said and Nietzsche said and Milton said, but he himself, unlike Joyce and T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, has nothing really new to add. All right —it’s all a mess and it’s too bad about the individual — so what? Most writers line themselves up along a solid gold bar like Ernest’s courage or Joseph Conrad’s art or D. H. Lawrence’s intense cohabitations, but Wolfe is too “smart” for this, and I mean smart in its most belittling and modern sense. Smart like Fadiman in the New Yorker, smart like the critics whom he so pretends to despise. However, the book doesn’t commit the cardinal sin: it doesn’t fail to live. But I’d like you to think sometime, how and in what way you think it is superior to such a piece of Zolaesque naturalism as Maugham’s “Of Human Bondage” or if it is superior at all….

Notice the marching tour de force through famous writers’ qualities, the masterful command and casual audacity on the question what will last the test of time and what won’t. If you’ve read great authors’ private letters, you will know that many can and regularly do this in their correspondence. They seek to understand, celebrate, size up, cut down. But for Fitzgerald it was more than interest, more than admiration, more than seeking to comprehend or to share his wisdom with his daughter. It was a zeal and hunger for the best elements he could emulate, borrow, or to use his word, thieve.

These two passages I have found and offered up here are from the very book ends of Fitzgerald’s professional life, one from age twenty-three and one from probably the final months of his life, two decades later. The import could not be more clear: Fitzgerald had an express, abiding passion to ingest and command the best elements of the world’s best writers.

So what if we just listened to Fitzgerald directly? What if we considered him according to his own lens, according to the tea leaves he himself left us. Set aside the psychological lens, the commercial lens, the lenses of political economy, Not-Hemingway, and the Great American Gatsby. Listen directly to him. What does listening directly to him do to our understanding? He pursued excellence in as many elements and facets of writing as he could. Though I can’t find specific evidence that he sought to master various genres, he perceived the constituent parts of genres to be these atomic elements on which he commented publicly and privately. Versality in these was the high achievement at the center of his literary ambition.

Suddenly, we can see his successes as a short story writer – even one who sometimes tried on the maudlin turn or the cutesie lift – as indispensable examples of his genius rather than as commercial compromises to be dismissed as filler between the grandes gestes of his novels. We cannot know Fitzgerald’s quality without admiring the excellence across the full breadth of his work.

There remains, down the years, one trenchant criticism of Fitzgerald that still needs to be addressed. Especially during his lifetime, Fitzgerald was disparaged even by his admirers as a man who could not conjure a single intellectual idea, as an Author Without Portfolio, even as he churned out beautiful stories and novels, as a kind of coward who studiously avoided the political topics of a lifetime that comprehended the Great Depression, the fireworks of anarchism, the rise of communism, and European cataclysm. The period in which he was alive was supremely fertile with such subject matter. It is hard to imagine a forty-four year period with richer soil to plow. But Fitzgerald wasn’t having it, and even his friends like the legendary American critic Edmund Wilson were openly frustrated. It is facially an unavoidably fair criticism. But as I considered his works, I found myself thinking that Fitzgerald had been underestimated.

I think this take misses the significance of Fitzgerald’s acute interest – likely his most consistent acute interest throughout his writing life – in attaining excellence across the métiers of writing, in different styles and elements of perfect prose. Even within literature, the critical class is absorbed with its own nose, with locating the Essential Quality of a writer and then in dismissing or discarding his work outside these boundaries. Fitzgerald’s project – his entire, self-avowed, openly declared project – was to understand what made English language writing excellent and important and to master each component so as to be able to write anything well. This is both a serious intellectual idea and a heroic undertaking. It is bigger than Criticism. It is bigger than the critical class. It is a backhanded slap that smites the critical project, because it says Your Value, in Gross, lies in Delineating Me, and I Refuse You.

During his lifetime, Fitzgerald was celebrated for his stories and for his first two novels and then not for Gatsby. Then everything got turned upside down.

Finally, it is time to turn things right side up again.