The Coddling of the American Mind or, Finally, The Kids Are Not Alright

Even before the Coronavirus Pandemic, We Were Making them Mentally Ill

This is a book about mental illness. Or, more accurately, about mass psychogenic illness or mass hysteria. Or, even more accurately, about induced mass mental illness.

By now you will have encountered — independently or otherwise — some version of the idea that today’s typical young person appears to believe, as compared to the comparable typical person of a prior time, that one’s objective in life is to discover the mental illness from which one suffers, and that this discovery is a living fulfillment, the transformational attainment of self-realization and becoming. Knowing how you are ill almost seems to be part of growing up and achievement of identity, like knowing if you’re a painter or a drawer, or a book reader or a gamer. It is now, in a word, a thing.

How did we get there? Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt have come to tell us.

The central claim of Coddling, persuasively argued, is this: Young Americans show up at college as socially anxious creatures woefully unprepared for any form of disagreeableness, including uncomfortable conversation. They are, by and large, emotionally immature, and they are neither accustomed to nor interested in debating ideas, in disagreeing with others on any substantive matter, or indeed in spending time with others who may disagree with them. Upon matriculation, universities make matters much worse. They take mentally unstable kids and teach them to behave in classically mentally ill modalities. In fact, universities teach young people to make themselves crazy. Young people enter university destabilized by social media, by a poor screen-time/in-person-time social ratio, and by helicopter parenting. The universities graduate their mania from anxious behaviors to the habits of full-blown mental illness. Specifically, young people are taught to embrace, live with, and rely all the time on what for decades have been well characterized cognitive distortions, including overgeneralizing, catastrophizing, fortune-telling, dichotomous thinking, and others. These habits of depressed, paralytically anxious, and suicidal populations have, instead of being treated as obstacles for the few to overcome, been imported, mainstreamed, normalized, and even celebrated for use by all. The consequences are awful. A polarized society becomes more polarized. Young people can’t function in conflict because they are convinced that disagreement is assault. A religion of shibboleths and taboos is born, with adherents from the left (chiefly) and the right (also) at ease with the notion that the only way to treat the Other is an Enemy who is to be ostracized, suppressed, and demolished.

What a world.

The book seeks to reveal and subvert what it calls Three Great Untruths:

1. Untruth of Fragility: “What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.”

2. Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: “Always trust your feelings.”

3. Untruth of Us vs. Them: Life is a battle between Good People and Evil People.

Greg Lukianoff, President of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Expression (FIRE), and Jonathan Haidt, Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at NYU Stern, are brave, scholarly, and kind, and so is their book. In it, they tackle a host of forbidden topics and expose rot in our culture without singling out or dressing down any villains. In that, they seem to practice the civility they crave. They also manage to pull off an erudite, academic march through relevant literature while making Coddling accessible to the general reader. Lukianoff and Haidt survey scholars from fields as diverse as education (Hanna Holborn Gray), neuroscience (David Eagleman), public intellection (Jonathan Rauch, Conor Friedersdorf, Radley Balko, Michelle Alexander), sociology (Herbert Marcuse, Emile Durkheim, Albert Bergesen, Bradley Campbell, Jason Manning), psychology (Jean Twenge, Derald Wing Sue of “microaggression” fame, Henri Tajfel, Angela Duckworth, whose Grit should assuredly compete with Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers for some millennium prize awarded for Glib Gaunt Gruel), law (Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw), philosophy (Kathryn Pauly Morgan), political science (Mark Lilla Shanto Iyengar, Masha Krupenkin, Steven Levitksy, Daniel Ziblatt), and linguistics (the inimitable John McWhorter).

They locate the paradigm shift on university campuses around 2013, when iGen (also known as Gen Z), born in 1995 and later, showed up at college. The authors observed that, starting in the late Aughts, university “[a][dminstrators often acted in ways that gave the impression that students were in constant danger and in need of protection from a variety of risks and discomforts.” Millenial students seemed to brush off this attempted conditioning as so much pablum. But, a few years later, iGen embraced or succumbed to the conditioning. Then the whole world started to change, quickly.

Students started demanding that disagreeable campus speakers be disinvited. Well, that was nothing new. But the basis for their demands changed. The “rationale for speech codes and speaker disinvitations [became] medicalized: Students claimed that certain kinds of speech — and even the content of some books and courses — interfered with their ability to function.” In short, triggerings. Previously, students would seek to block speakers who espoused, in their opinions, “evil ideas,” but “they were not saying [as they started to do about ten years ago] that members of the school community would be harmed by the speaker’s visit or by exposure to ideas.” Not only this, but in a variety of accelerating incidents, both students and faculty members began to pummel one another for offenses as minor as poor word choice in private letters or public articles, hurling accusations of bloody murder and demanding article retraction, resignation, termination, and humiliation when unpleasant ideas were apparently — emphasis on apparently — considered, weighed, offered, and, even, sometimes, overtly rejected. Just the act of public contemplation of a thought could break a university member into intellectual jail.

Coddling argues that at least two things happened to conspire to make all this possible. First, moral culpability shifted, basically, from intent to effect. Set aside what you meant to do or convey, it is the impact that counts. This change in thinking is now the explicit aim of many public thought leaders. Not only that, but the quantum and nature of the effect is measurable only and exclusively by the person who perceives the effect. In short, if the Queen of Hearts feels you insulted her, off with your head!

Second, emotional safety was elevated to the same plane as physical safety. By now all of us have heard or read the phrase “actual violence” or “literal violence” in cases in which it actually and literally does not fit. What is meant on these occasions is often plain enough: such and such a phrase or idea can lead to the perpetuation of a system or set of habits or behaviors that lead to outcomes that are harmful. The shorthand is “actual violence.” Which includes insult, slight, or disagreeableness. And this is and must now be acknowledged, or so the theory goes, as equivalent in consequence and degree as a punch.

Put these two concepts together, and you have a powerful concoction: any person can, whenever one feels like it, decide that an insult has been visited, that harm has obtained, and that the harm is of X type and Y degree. Imagine a sort of universal and portable, iPhone-sized Star Chamber. Or, perhaps better, everyone gets to be Judge Dredd: don’t like what you see or feel happened at any time, and you can be judge, jury, and executioner.

To make matters worse, harm is everywhere! Educators now teach young people cognitive distortions as elements of regular living. The result is absolute intolerance for someone else’s disagreeable ideas. For (a lifted from life) example: if a pro-life speaker comes to campus, a student might attack the students who invited her to speak by accusing them of having the actual blood of women on their hands. Lukianoff and Haidt point out this is a kind of catastrophization as well as an act of dichotomous thinking and labeling, among other cognitive distortions.

One thing Lukianoff and Haidt don’t quite do is connect the dots between the lexicon of “harm” and the legal armature that becomes available as a result. The invocation of “harm” as a consequence of speech, ideas, and nonviolent communication has extraordinary legal import. Invocation of harm allows the invocation of state action. Since state action exists, at bottom, to prevent harm, the apparatus of State (and other Authority) springs to life. So, if you don’t like the reading assigned to you, you can assert “harm” and appeal to the legal apparatus to rescue you and formally punish the person who assigned the reading.

Lukianoff and Haidt argue that this coddling of the American mind is hobbling the future of an entire generation of young people. They will not be prepared for life, for love, for learning. They will be poor citizens, bad leaders, and intolerant neighbors. They will be, somehow, useless to themselves and to the rest of us. They will be, perhaps, the kinds of people the Greeks used to call ithiotis, or idiot.

When I picked up the book, I had expected it to be a kind of intellectual successor to Robert Hughes’s marvelous Culture of Complaint (1994), which, when I read it together with Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s 1991 Disuniting of America in high school, as the twin phenomena of Multiculturalism and Political Correctness became influential, changed my life at a very young age, in that it turned me on to what I knew, even at that time, would be an unfolding of a societal hot war that would last at least throughout my life. Well, I think Coddling is, in fact, a kind of follow-up to Culture of Complaint, and a worthy one, too, sounding an alarm on the up-leveled Victim Competition that seems to appear in nearly every corner of our society.

The book is much more sensitively rendered than Culture of Complaint, at least as I remember it. I think of Hughes, now dead, as a kind of proudly cantankerous fellow, and that is not my impression of either Lukianoff, whom I have met (and who gifted me a copy of his book) or Haidt, whom I have not. Perhaps the most gemlike discovery in this book is of that mold: the authors share an insight, unique in my reading, that there are two kinds of Identity Politics that must not be confused. This is important because there is now an entire sub-literature on whether identity politics is dividing us unnecessarily or, on the other hand, whether those who claim such politics are dividing us are willfully or ignorantly blind to the idea that all politics is identity politics or that criticizing identity politics is itself some kind of reification of existing hierarchies. Lukianoff and Haidt solve it all at once. Their insight is that there is a distinction to be made between Common Humanity Identity Politics and Common Enemy Identity Politics. One nurtures the tribe while bringing us together. The other activates the tribe by nominating the devil in the other.

Like many important truths, this insight is obvious once you see it, but one feels one was rudderless before seeing it.

One question, as I read Coddling of the American Mind, was whether the authors went quite as far as they would have liked to go. Over and over again, they (and others they quoted and cited, like Laura Kipnis) sought to end the argument by showing that all of this coddling was doing a huge disservice to young people because, as they enter the “real world” after university, they will be confronted with cold conflict, harsh feedback, daily cognitive dissonance, the disappointments of everyday intimate and impersonal relationships and encounters, and the inconveniences and blows and setbacks attendant in any free-thinking, free-market society. The point, as such, is something like “Today’s parenting trends and nanny-state-university administrations are not adequately preparing young people for life. They will suffer forever as a consequence.” I agree this seems true. But putting down their pens there, I think, disserves what I imagine might be their actual objective in two ways.

First, the parties on the other side of the argument imagine — correctly or fantastically — that they can change the world in such a way as to make some claims or truths taboo in the “real world,” too. Their vision for the future includes seizing and transferring resources (wealth and otherwise) from those they perceive as having “privilege” to those who don’t. Their aim is to make others pay for their good intentions. Their plan is to make it impossible to have uncomfortable conversations anywhere, not just on campus. And they are, in part, succeeding. One need look only at some of the so-called “inclusiveness” training on corporate campuses to see how outlandish and silly this can get. Viewpoint diversity is explicitly suspected and casually ostracized in the daily life of many businesses. Painful self-censorship for reasonable views is now manifest in professional life. In other words, the disease Lukianoff and Haidt are exposing has already escaped the university setting and followed its graduates to fields such as business and law. The problem is therefore self-evident: Coddling only partially correctly argues that the hobbling of young people in these intellectually and emotionally infantilizing ways will harm their life prospects. In at least some quarters, their emergent mores and habits will, in fact, make them so much empowered royalty.

Second, I had the impression (though it is only my impression, which is a function of speculation, hypothesis, and a small dose of atmospheric reading of interviews, etc., so we must allow that it could be a misimpression) that Lukianoff and Haidt wanted to go further. I felt perhaps they wanted to say that “not only is this coddling an impractical and unforgivable disfavor to young people, it is also morally bankrupt, childish, and wrong.” They don’t. Maybe that’s for the next book. Or maybe they can’t, because their book is about a systemic failure of viewpoint diversity (which coddling makes impossible). Or maybe they don’t believe as much, which I can’t quite reconcile with the book as I read it (see my prior parenthetic). Or maybe they think they do, in which case I think they didn’t do so clearly enough. Or maybe they wanted to and were warned off by their editors, which would be hilarious.

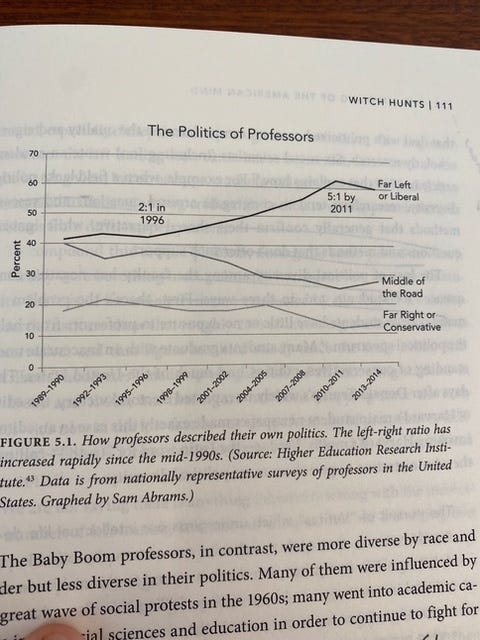

Lukianoff and Haidt do seem, like some other academics I have read and reviewed here or elsewhere, to locate a whole helluva lot of the problem in universities. Lukianoff and Haidt are not only university creatures; they have devoted much of their lives to solving the problems of universities. And the problems in universities are evident, increasingly well quantified, and horizontally systemic in that schools pump out graduates who later lead the economy and the polis. The chart appended here shows the increasing left-domination of the academy. (The commentary around it demonstrates the well-characterized consequences and impacts of politically one-side-dominant faculty entrenchments, too.) And even this chart doesn’t reveal the even more startling ratios in certain fields and geographies. “In . . . academic psychology, the left-to-right ratio was between two to one and four to one from the 1930s through the mid-1990s, but then it began to shoot upward, reaching seventeen to one by 2016. The ratios in other core fields in the humanities and social sciences are nearly all above ten to one. The imbalance is larger at more prestigious universities and in New England.” This is all very important and should be. I also found myself wishing that more people like Lukianoff and Haidt, even if not they themselves, would poke their heads out of the towers and see what’s going on around the rest of the world, too.

In fairness, the book does poke its head off-campus, if only to observe, especially in one very good chapter, the difference between on-campus hysteria from the left and off-campus hysteria (as it relates to on-campus doings) on the right. But it’s still all to do with the university setting.

Coddling is also much more a book about parenting than I had expected. Indeed, probably a solid quarter of the book is devoted to a kind of Antifragile Parenting Handbook. Lukianoff and Haidt are, it seems to me, natural optimists, which trait I admire. They find that kids are naturally antifragile and are turned into eggshells by woefully inattentive parenting (of the awfully traumatic household variety) and helicopter-overparenting (of the over-programmed and safetyist variety). They make the case that, by the time the kids arrive in college, they have been hamstrung by coddling. They can’t fend for themselves in complicated (or even not that complicated) social or societally dynamic situations. They live in and by fear. They are immature in comparison to their prior cohort equivalents, behaving at eighteen years old the way the fifteen year old of yesteryear would have have behaved. They are inclined to seek succor, support, and protection with the authorities if they feel slighted or wounded. And, perhaps most tragically, they have already been trained to see emotional threat or disappointment as aggressions. Lukianoff and Haidt trace the emergence of a broad paradigm shift in the underlying culture of how Americans deal with slight. They map the change to the oft-used axis of Dignity Culture vs. Honor Culture. In Dignity Culture, people are trained and habituated to shrug off insult because they are possessed with enough internal dignity that their senses of self easily survive most offenses. The authors cite the famous “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never harm me” as the playground saying that helps imbue us with this powerful Dignity culture from a tiny age. By contrast, in Honor Culture, even small insults may result in fatal duels and other tragic idiocies.

Well, I’ll be. I noticed early this past school year, on a parental visit to my kid’s classroom, a sign on the wall that read: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will truly harm me.” I couldn’t believe it. An entire value system upended. All of us could perceive the Good Intentions. But, finally, there it was, in evidence: the coddling of the American elementary school mind.

Nice review. Thanks for penning.

Haidt is such a great messenger. He is always measured and kind in his delivery. He's been on all my favorite podcasts recently promoting his new article in the Atlantic, "After Babel." The best one I've heard is his talk with Coleman Hughes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsW7q12WJBs

I also love Lukianoff. One of his close friends, Professor Lyell Asher at Lewis & Clark College, has done a riveting video series connecting Teacher's College and other Ed Schools to many of these trends: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0hybqg81n-M&t=416s

Good to read you.